Summary: The investor psychology behind Bored Apes – and how to be a better investor than status-seeking monkeys. Subscribe here and follow me to get more mental tips and tricks.

“People are status-seeking monkeys.”

So begins the 20,000-word blog post from the Silicon Valley pioneer Eugene Wei. His post is so densely packed with insight that it took me a week to read it, savoring little morsels each day over lunch.

To repeat: people are status-seeking monkeys.

By “status,” he means “social standing.” Think about your car, your job, your house, your clothes, your alma mater: whether we like it or not, these are all indicators of status, our place in society.

Wei’s insight is that online social networks are largely status games.

They hook us in with some kind of “social capital” (likes, followers, retweets), an ego-feeding reward that gets us addicted to playing the game, so that we build their businesses for them.

I’m guilty of this. I take great pride in my LinkedIn following, which I’ve been cultivating for 20 years. I was even prouder when I was asked to become a LinkedIn Influencer (just like Bill Gates and Tony Robbins, I thought), and thrilled when my first few influencer posts received gobs of traffic.

Then the traffic died down, and only after reading Wei’s post did I realize LinkedIn played me like a fiddle: the algorithms favor new users to get them hooked, then drop back your promotion once you’re established.

You probably have your own story like this. It feels really good to post something that gets a lot of likes or shares. You think, I matter. You’re playing their game, even if you don’t realize it’s a game. The status game.

Status is ego-feeding. It’s literally adding to your ego, your sense of self. That’s powerful and addictive, because more status — like a fancy car, a lucrative career, or being an Instagram influencer — can mean more social capital.

Wei calls companies like Facebook and Snapchat “Status as a Service” (StaaS) businesses. Then he drops this wisdom bomb:

Social capital is, in many ways, a leading indicator of financial capital.

In other words, if you are working hard for Twitter or Instagram, playing their status game, you are giving them your attention, and your attention can be monetized.

They give you status, you give them eyeballs. And eyeballs make money.

When companies are successful at getting people to play their status game (i.e., participate in their social network), soon network effects kick in, and the money soon follows.

Hang on a sec. Network effects? Status? Money?

This sounds a lot like blockchain.

And in fact, Wei argues, it is.

The OG Proof of Work

Social networks work similarly to blockchains:

- Instead of tokens, they reward you with “likes” and “retweets.”

- To farm these tokens, you have to provide some new “proof of work” (a blog post, status update, or selfie).

- They make it easy to farm tokens in the beginning, but then it gets more difficult over time (built-in scarcity, like bitcoin).

Just as one could say that tokens have no value, one could say that retweets have no value … but they do, because they reflect human attention, and attention = money.

Likewise, tokens have value – especially if they get to a certain size and velocity (i.e., achieve network effects) – because they represent human attention in a blockchain project or technology.

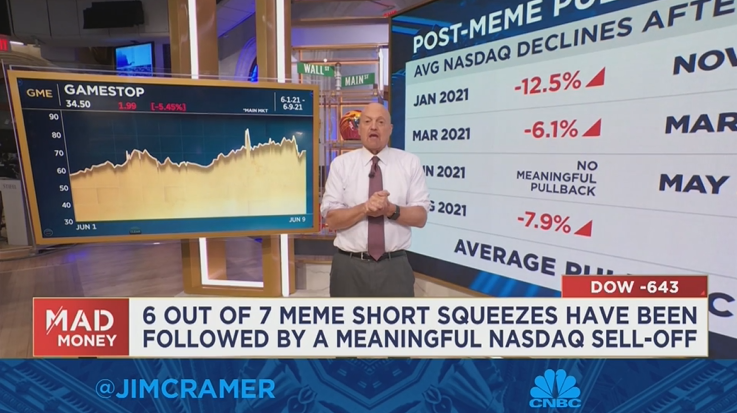

This can also explain the rise of meme stocks, which are a kind of status game for those “in the know.” It also explains the ridiculous valuation of companies who are very good at commanding attention, like Tesla.

(As a Tesla owner, I’m ashamed to admit that even driving a Tesla is a massive status game: you look at every poor chump driving their gasoline-powered cars like early automobile owners must have looked at horse-drawn carriages.)

Just as bitcoin requires Proof of Work (fast computers solving math problems), social networks require their own proof of work (LinkedIn makes me feed it a new influencer blog post each week, in return for that sweet sweet status).

As crypto investors, it pays for us to identify which crypto projects are explicitly wired into our status-seeking circuits.

Through the lens of status, many of the mysteries about crypto investing are suddenly explained.

Bored Apes are Status-Seeking Monkeys

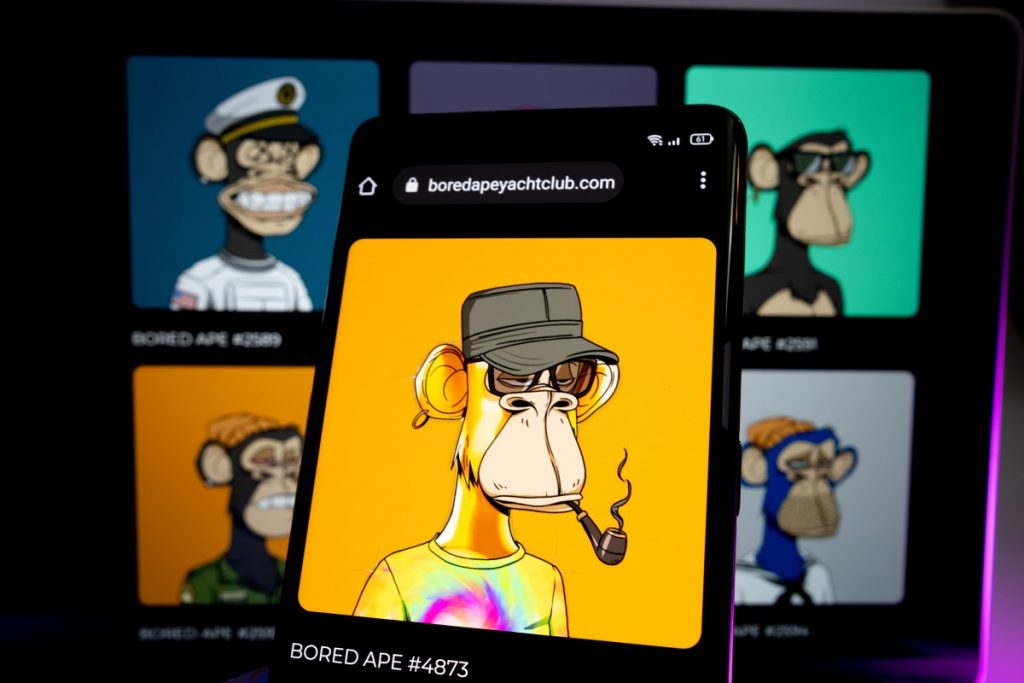

A prime example is the Bored Ape Yacht Club. Just understanding the name is a kind of status signal:

- Apes = internet slang for investors who supposedly don’t know anything

- Yachts = the ultimate status symbol of the fabulously wealthy

- Plus, they’ve made so much money that they’re bored.

Indeed, many of the Bored Apes are dressed in comically exaggerated rich-person garb:

But the status game goes much further, because to “own” one of these images costs real money (starting at $1500, as of this writing), showing that you are, in some way, a bored ape.

It gets better, because owning a Bored Ape gets you into an online members-only area, as well as IRL members-only events. You can remix them into your own creative projects, like Eminem and Snoop Dogg are doing.

Bored Apes are a triple-decker status sandwich.

The same goes for much of the NFT market (and much of the traditional art market as well). If you buy these things, you’re in the “club.” So the thing may rise in value, as long as more people still want to be in the club.

This is why collectibles are such difficult investments, and why I would never put more than 1% of my total investments into NFTs (read our NFT guide here). They’re too finicky.

Let’s take another blockchain project like the Ethereum Name Service, which is also a status game. Rather than using your long hexadecimal wallet address (0x4862Bf…), you can just shorten it with an ENS name (john.eth).

In crypto circles, it feels good to have a .eth address, because it shows you’re in the club. It signals that you’re an early adopter. You get it.

But ENS is also useful, because they could become the domain names of the future. There’s only one john.eth; if you don’t claim it now, it may be gone forever.

In that sense, ENS is also speculative, because just like early domain names, you have people buying up every potentially valuable name, in hopes they might resell them later for outrageous sums.

Bored Apes and ENS are two very different projects. Although they’re both built on blockchain, they look almost nothing alike. You’ve got to look for the underlying status game.

Knowing that “people are status-seeking monkeys” can help make us better crypto investors, because we can identify the projects that are playing the status game.

Investing in Status is Like Investing in Social

It’s tricky to invest in social media networks, because they tend to rise and fall. (If you don’t remember MySpace, my point exactly.)

Is TWTR stock a good buy, when it’s currently suing Elon Musk to buy it? Is META a good buy, when it’s trying to reinvent itself into an imaginary industry? Is SNAP a good buy, when it’s down 75% this year and laying off 20% of the company?

The problem with building a business on attention is that people have short attention spans.

This goes double in the light-speed world of crypto investing. We often joke that your perception of time changes when you’re working in the crypto industry:

For this reason, investing in status blockchains is tricky, because crypto is driven by early adopters. As soon as something gets too popular, they’ll be off to something new.

The open-source nature of crypto also means that status blockchains are easy to copycat. Witness the litany of Bored Ape ripoff projects, like Women Ape Yacht Club, which is currently a Top 10 NFT collection, despite having no official affiliation with BAYC.

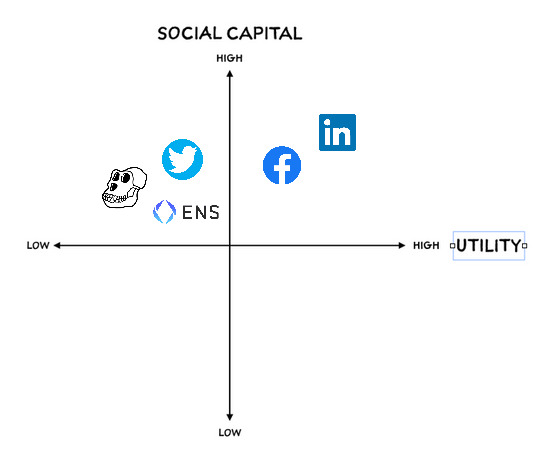

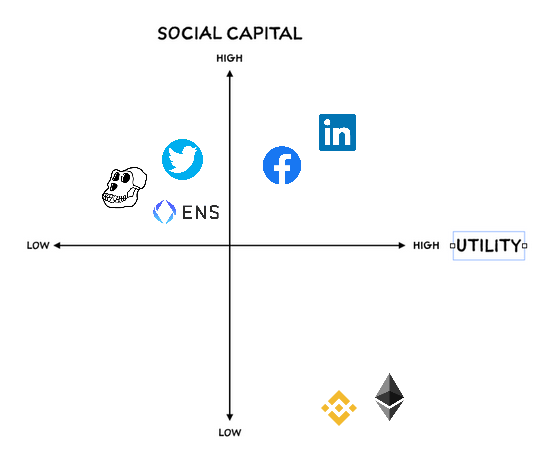

Wei uses this helpful diagram to show that successful social networks have a combination of entertainment and utility (i.e., status games and useful stuff):

Facebook may be a popularity contest (entertainment), but it’s also a place where you can keep up with distant friends and family members (usefulness).

Similarly, we can map “status blockchains” like BAYC and ENS on this same chart:

With tokens like ETH and BNB, we have real utility, and virtually no status (especially if you hold them anonymously):

In the bottom left quadrant would be the vast majority of crapcoins. (Low social capital, low utility.)

As crypto investors, we want to go as high up on the Utility axis as we can.

This means we avoid tokens built solely on status, as that’s a Jenga tower waiting to collapse. The only long-term plan for status projects is to build in more utility, which may make them less entertaining and they’ll collapse anyway.

When evaluating crypto investments on this status/utility grid, opt for utility, not status.

The 40,000-Foot View

Let’s go up to cruising altitude and look at the crypto landscape over the last ten years. What types of projects have not only thrived, but endured?

The most successful blockchain projects have real utility: either they allow people to build new projects (all the L1s), or they allow people to use their crypto to earn more crypto (CEXes, DEXes, DeFi, and the like).

True, there are second-order status effects at work: when we make a lot of money in crypto, people look at us like geniuses. But the projects aren’t based on making you look good to other people.

I’m not saying status is bad, or status is wrong. Status is just a game, one that ultimately matters very little. But when we’re caught up in the game, it feels like it matters a lot.

Eventually, we snap out of it, we get bored, or we notice all the cool kids have left. Status is fickle that way.

For this reason, my investing principle is to avoid crypto projects based solely on status, and favor projects based on utility (i.e., real-world value).

Don’t be a monkey: leave your ego at the door.